The Dog Training World: science is BIG

I've fallen behind in my blogging; my excuse is that I'm spending much more of my time these days in the Dog Training World (DTW). Like any other community or specialized subculture, DTW has its own idiosyncrasies. As someone who has already explored several brave, if not new, worlds (competitive running, indie films, grass roots activism), I'm not too weirded out by DTW. Yet.

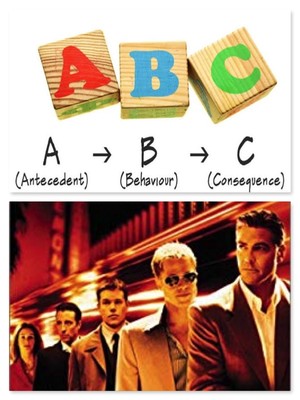

The people who populate DTW are very friendly, supportive and enthusiastic. Most of them are also science-obsessed, or animal-behaviour-science obsessed, anyway. In every podcast and on-line tutorial, a DTW expert will advise, "Go back to the science. Go back to ABC." ABC, in case you're wondering, stands for Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence, a model for both understanding and training animal behaviour.

Personally, as a student of the humanities, I prefer to think of Hollywood heist movies when contemplating dog training scenarios. Oceans 11 springs to mind: The Set Up! The Action! The Unexpected/expected Twist! The Pay Off! Which sets the stage for The Sequel! And then The Second Sequel!... Dog training is a NeverEnding Story.

Still, the applied science stuff is very, very useful. So I enjoy the endless conversations with other animal trainers.

That said, I'm not convinced that science should be a big selling point in marketing DTW. A lot of trainers promote their services this way, using expressions like "scientifically proven." My favourite promo statement proclaims "we keep far FAR away from superstitious training and quack methodologies by staying firmly rooted in behavioural science." Now, it turns out that "superstitious behaviour" is a term used by B.F. Skinner, but when I first read this I immediately wanted to know about "superstitious training." Is there coin tossing? Animal training tarot cards? Lucky underpants? What am I missing?

There's a few reasons I'm leery of the "science sells" approach. It's ubiquitous, for one thing. It's hard to find a training school that doesn't mention science. And a lot of people can't differentiate between the kinds of scientific claims being made.

I mentioned this to my friend, Maureen, but she disagreed; she thought science would be salient for some people, just not for anyone she respected. Which brings me to my second point, i.e. the Science Skeptics. We can be found on all points of the political spectrum, not only on the climate-change-denying Far Right. For instance, I got the summer off to a productive start by reading "Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That's Rewriting the Story." Distrust of scientific narratives can be healthy, especially for a marginalized, disempowered class (a category in which some might believe animals belong). Science is not always and automatically perceived as a progressive force for good, mostly because often it hasn't been.

More important than the question of whether science sells is whether science-based arguments are a good way to persuade people to behave in certain ways with their dogs. To which I think the answer is a qualified 'yes.' Although I keep in mind that people usually get pets for companionship and pleasure, not as science projects.

The corner of DTW that I am currently exploring is known, in the trade, as the positive reinforcement quadrant. So I spend a lot of time explaining, say, why reprimanding the dog and/or doing a 'leash pop' is not my first choice to deal with barking and lunging. My spiel to clients does not start "Studies show that aversive techniques result in more problems with fear and aggression in dogs." Nor do I begin by reviewing the data on the efficacy of positive reinforcement training. (I was bored just writing those sentences).

Usually, I trot out my favourite science story (so far): The Negativity Bias. I don't mention the story title right off the bat, because let's face it, too blah. Here's an example of how it usually goes. My most recent clients using the No!/leash pop method with their dog were a couple of actors. "Think about when you give a performance," I suggested. "Six of your colleagues shower you with compliments, but one, the one with seniority and star power, is less enthusiastic. She just shrugs her shoulders, and makes a disparaging remark. Which reaction sticks with you?"

Well, for the emotionally sensitive actors, no question; they are crushed by the criticism. That's what they'll remember, and it will stress them out. This is true for most people, and most mammals, for that matter. It's at this point that I mention The Negativity Bias, and explain that we — humans and dogs — tend to place more importance on negative info and experiences than positive ones. Threatening stuff is more relevant to our survival, from an evolutionary standpoint. Probably.

The actors get it: bad performance reviews are super-distressing, so while their dog's on-leash barking may decrease, he might be more unsettled and 'act out' in other situations. His underlying animus towards other dogs has not changed, but his feelings towards his people might well have.

I like The Negativity Bias because it can be tailored to individuals: bureaucrats, fashionistas, landscape gardeners, and lawyers (yes, even lawyers) all get a version they can personally connect with. Also, the explanation puts dogs and humans in the same boat. Creating inter-species empathy is as important to me, maybe more, as good behavioural outcomes (they are not unrelated, in my opinion).

That said, sometimes I work with a client who seems to have no sense of their own vulnerability, bringing vividly to mind myself in my 20s. With them I'm likely to play the Results Card, and urge them to JUST TRY positive methods first to see where they get with their dog.

At no point do I mention my lucky underpants.

For a look at dogs and the negativity bias, and an excellent (science-based!) dog blog: https://thesciencedog.wordpress.com/2017/07/18/do-dogs-have-a-negativity-bias/

For a video that cropped up when I was researching the negativity bias, and that I sometimes share with those who, like me, think their dogs are a lot like toddlers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FC4qRD1vn8

For an explanation of superstitious behaviour in animals: https://ethology.eu/superstitious-behavior-in-animal-training/

And look for the book Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That's Rewriting the Story, by Angela Saini, Beacon Press, 2017.

Want to make a comment and avoid registering with Disqus? Click on 'join the discussion' and in the name field at the bottom of the form check "I'd rather post as a guest."