The Affordable (Canine) Care Act:

when to say no to the vet

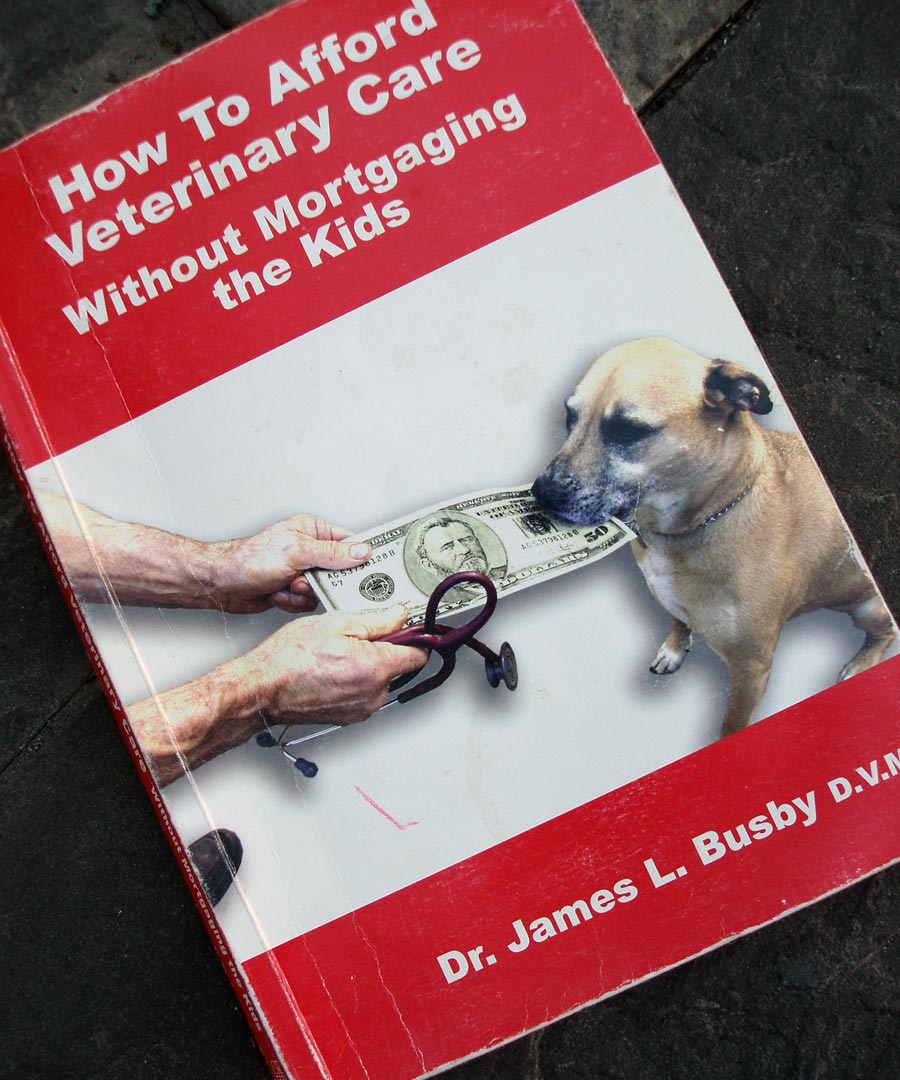

How to Afford Veterinary Care Without Mortgaging the Kids by Dr. James L. Busby D.V.M.

Sometimes, when contemplating my pet health dilemma du jour — runny poop, gummy eyes, or something more serious — I wish I had a cantankerous-but-kind uncle whom I could call for advice. I would disagree with him (we're both highly opinionated), but his BS detector would be a tad more knowledgeable mine. So I'd consult him regularly.

Instead, I have James Busby's book, How To Afford Veterinary Care Without Mortgaging the Kids. When I'm wondering whether a visit to the vet's is medically useful or just a sop to my anxiety, I page through this book first. Then I consult the dozen or so other dog health books I hypochondriacally keep on hand.

Busby, like me, does not seem overly fond of veterinarians, although he actually is one (or was one; I'm not sure he's still practicing). His great grandfather was "a horse doctor with a thing for Boston Terriers," and his father and uncle were country vets, so he has a multi-generational perspective. According to Dr. Busby, most vets used to be honest — past tense. They cared about keeping your animal as healthy as possible. Back in the day, they did this without busting your budget or "incurring undue risk and pain to your pet."

Now, writes Busby, many clinics are focussed on the bottom line, with practices that are "unethical and outright fraudulent." They "push as many procedures and services... as the pet owner will tolerate, in order to generate as large a cash return as possible."

My vet doesn't do this of course, and probably yours doesn't either... Except that, as I page through the book, many of the procedures Busby dismisses as unnecessary are routinely recommended ones. I usually refuse them, and my vet doesn't insist (as Busby advises, "avoid veterinarians who try to shame you"). But sometimes it feels awkward saying 'no' to the vet.

I remember the first time I said no (with my first dog, and my first vet). I had brought in my puppy because I had discovered a small unidentifiable object sticking out of her back, firmly lodged in her coat. It looked like a tiny metallic brush bristle; she yelped when I touched it. Mysterious.

But not to the vet. "Oh," said he. "That's her microchip. It migrated."

"The microchip can migrate?" I asked. No possibility of microchip migration had been mentioned when it was inserted.

"Oh, yes. But usually not out. Probably we didn't insert it properly. Do you want me to re-do it?"

"No!" I said. Later, as a dog walker, it became clear that migrating microchips are fairly common. When Animal Control officers scan a dog, they always start at the back of the dog's neck and scan along the spine to the butt. Vets should disclose that microchips, like dogs, might stray. If you don't want a chip wandering around in your dog, an old fashioned name tag is your best bet.

My current home-pack: three dogs, three years of age and under, so no pricey health problems — yet.

Dr. Busby doesn't discuss microchips, although he reviews most common veterinary practices and pet health problems. He's got a lot of good advice about what not to do. He covers when not to vaccinate, when to forgo x-rays in favour of rest and painkillers, when not to ask for/accept antibiotics, when not to worry about diarrhea, and when to use over the counter drugs.

Busby is dedicated to affordable care. He is annoyed by vets who demand check ups to dispense flea or heart worm medications, or re-testing to renew prescriptions. Most aggravating to him are vets who propose tests when clients can't afford the treatment of the disease or problem being tested for.

Busby suggests "find someone more reasonable and caring." If you live in a North American urban centre, finding a "reasonable" veterinary clinic can be a challenge. Many of my dog walking clients (I'm talking about the humans here) are uncomfortable at their vet's. They feel irresponsible or callous if they don't follow the vet's recommendations, and miserly if they express reservations about costs. Maybe a more "patient-centered" medical model (with the 'patient' being the pet and their human) should be taught at veterinary colleges.

Clinic visits often feel like a cash grab. There's the not-so-subtle pressure to purchase products, from ear washes to special foods, not to mention pricey and unnecessary preventatives. If, like mine, your downtown neighbourhood is too polluted for mosquitoes to inhabit, your dog probably doesn't need heartworm protection.

Drugs, which are often identical to the ones prescribed for humans, are extra expensive at the vet's. You can request your vet write you a prescription to take to the local drugstore, but it's an awkward acknowledgement that you feel you're being gouged — which you are.

There's also the baffling difference in amounts charged amongst vet clinics, and in particular the rural/urban divide. Overhead and real estate alone cannot account for the staggering price differentials. Around twenty five years ago, when I was outraged at the cost of some procedure, I asked whether there were any standards. I was shown a booklet of price 'guidelines,' which I was told at the time was available at any clinic. I haven't seen (or asked for) one since.

While researching this blog post, I learned that the Ontario Veterinary Medical Association produces "a suggested fee guide" for OVMA members only (i.e., not for the public). It's designed to help vets "by breaking down the cost of delivering the service so vets don’t have to figure this out themselves." According to the OVMA, it's never been publicly available. Maybe it's time it should be.

Once the vet delivers a diagnosis, I like to consider natural treatments. (I did mention my hypochondria, right?)

In the meantime, how can we reduce the cost of our vet bills? Short of launching a collective activist campaign (my favourite fantasy), here are a few tips, in addition to Busby's. When vets suggest multiple tests to "rule out" various conditions, ask which condition is most common and test for that first. Also ask how potential ailments are treated, because often the same remedy is recommended regardless of the the underlying cause (dreaded steroids spring to mind). Depending on your bank balance, it may be best to skip tests and go straight to treatment.

Whenever the vet recommends a more expensive or invasive test, I ask in what percentage of cases the test reveals useful information, and how often the results are inconclusive. Vets can be coy; coaxing may be required. "Just guestimate; anecdotal information is great," I say. That way, when the ultra sound doesn't show anything (except that there are no obvious issues), I don't feel like I've flushed $700 down the toilet in an uninformed way.

Steer clear of clinics where there's a larger number of veterinarians, especially if there's a two-tier structure (partners, associates) and a targeted amount of billing for each vet. Figuring out a clinic's business model can be tricky, but a lot can be gleaned just by chatting with staff. Also at the dog park — when I heard one vet referred to as running the "gold plated cadillac clinic," I crossed him off my list.

A couple of more tips, not about saving money but about staying sane. Write down everything the vet says. If your pet is ill or injured, you're going to be mulling over everything endlessly until the situation resolves. A written record will help you formulate questions and, eventually, a game plan. And don't make decisions on the spot; if you're feeling pressured, ask if there are any serious medical consequences to waiting.

Busby calls himself an "old, country vet." My urban vet is old school enough to pencil appointments into a calendar rather than book them on a computer, and he takes a non-invasive, minimalist approach. Sometimes he charges me for one check up when he's looked at two of my dogs, and he always encourages me to get a second opinion if we seem stalled. I also consult a mobile vet who focuses on holistic health care and who often surprises me with the smallness of his bill. So there are reasonable vets out there, but the current popular business model makes them few and far between.

Every vet has his/her drawbacks, and Busby is no exception. His language is often colourful, bordering on tactless. When writing about protein requirements for dogs, he points out that "compared to a sled dog running many miles daily, your animal is probably a pansy." He doesn't think your pansy needs a high protein diet. Also, some of his advice strikes me as dated and unsound, for instance when he explains how to "house break" your dog "with a minimum of abuse" — basically by shaming your dog.

Despite these flaws, I like How To Afford Veterinary Care Without Mortgaging the Kids. Whenever I peruse it, I feel I like I can and should be saying no more often, and I say this as someone who has neither a mortgage nor children. Busby reminds us it's not only cheaper to say no, it's often better for the long term health of our pets.

How to Afford Veterinary Care Without Mortgaging the Kids, by Dr. James L. Busby, is available through Amazon and the Toronto Public Library system.

Other resources in Ontario: https://www.torontohumanesociety.com/pdfs/Cannot_Afford_Care.pdf

Want to make a comment and avoid registering with Disqus? Click on 'join the discussion,' and in the name field at the bottom of the form, check "I'd rather post as a guest." A name and email address are still required.